Docking

Your ability to dock well is the key to your reputation.

For many people docking their boat is one of the most trying experiences to be had on the water. Attempting to tie up to a busy fuel dock on a windy weekend day can test anyone's piloting skills.

Let's face it, you may be the greatest captain on the planet, but your ability to dock well is the key to your reputation.

The things you need to notice when you are about to dock is where you intend to tie up, where other boats are, what the wind is doing, and to a lesser extent what the current is doing.

- Look and see how much room you have to maneuver your vessel around the area you intend to dock.

- Docking next to a long open pier is usually going to be easier than backing into a narrow slip in a confined marina.

- Are other boats leaving or entering the area you need to turn? How other boats are tied up or moving can greatly alter your intended steering and docking.

- Knowing which way the wind is blowing can greatly aid your docking. When coming alongside a pier with the wind in your face, head in at a steep angle to the pier and turn sharply at the last moment to avoid being blown out by the wind. If the wind is at your stern, come into the dock at a narrow angle and let the wind do the work of pushing your boat up against the dock.

- Current can also effect your docking in a similar fashion to wind, and in some areas can preclude you from docking at all in low water. Consult your tide tables, especially when traveling in new waters.

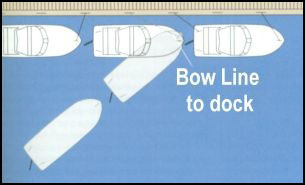

At all times, maintain no more than steerage speeds and try and have some crew ready with lines to tie off immediately. Using your lines to assist in docking can save a great deal of time and energy. Lines can be used as simple fulcrums to help bring either end of your boat to the dock. Let the lines do the work.

Like the people who run them, all boats differ in their docking characteristics to one extent or another.

And, the distinctions are particularly significant among three separate types: single-screw, keel-equipped powerboats and sailboats; single-screw planing hulls of moderate draft powered by a single outboard or stern drive; and keel-less powerboats driven by twin engines, whether inboards, outboards, or stern drives.

Covering all three types (and the variations within each) would be impossible in one section, so we're going to restrict ourselves to single engines this time around.

If you are routinely experiencing frustration and anxiety when entering slips or tying up to docks, the very first step is to give yourself a break: handling a boat - any boat - in tight quarters is difficult, particularly if you've got an audience and especially if you have to deal with wind and/or current.

Sure, launch operators and charter boat skippers who make 500-1,000 landings a year are good at it, but why should you be? Your total is probably more like 50 dockings annually, and expecting yourself to be perfect is unrealistic.

So, as you're going into a docking situation, it's better to relax and admit to yourself that you're probably going to make a mistake. That step in itself should help you calm down and, more importantly, slow down. Only good can come of your being more deliberate and more forgiving of yourself and your crew.

Next to patience and self-control, your biggest ally in docking maneuvers is nylon line. If, early on in the process, you (or a crew member) can connect your boat to the targeted dock or piling, and if you then know what to do with the throttle and steering wheel, you've got it made.

Spring Lines

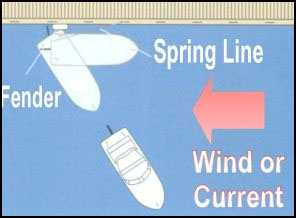

Here are some examples, all involving "spring" lines, a much-misunderstood term that simply means lines against which the boat can "work," thus ending up in the right position.

You are heading for a fuel dock consisting of a bulkhead of pilings and rip-rap. The problem is, you have to hit a gap between a 32' power cruiser and a 20' sailboat that are already tied up. And, to complicate matters, there's a 15-knot wind blowing directly off the shore.

The dock attendant is on hand and looking nervous because you aren't going to have more than 8' of clearance fore and aft. Don't worry! Ask one of your crew to throw him a line that is already cleated and coiled at the port rail forward, (preparation is 75% of the battle). As the dock attendant grabs the tag end of your line, ask him to attach it to a piling or cleat aft of the space into which you must fit.

Now, with the line secured at the dock and your wheel turned hard away from the dock (to starboard in this example), just put your boat in forward gear, at idle speed.

Miracle upon miracles, your boat will start moving sideways, into the allotted space! If you're working against current or wind and your progress is too slow, just advance the throttle slightly. You can also make small adjustments in your approach angle and speed by turning the wheel slowly one way or the other.

And, if it looks as if you're going to be too far forward of "the slot," momentarily shift into neutral, take up the slack that will immediately develop in the spring line, recleat the line again, and put the engine into reverse once more. If you're too close at the stern, carry out the same maneuver, but slack off the spring line.

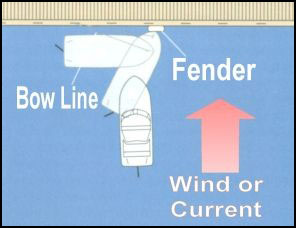

Now, suppose there has been a 90 to 180 degree wind shift while you fueled up and went for groceries at the store down the block from the marina. When you get back to the boat, there's a 15-knot wind blowing directly down the dock.

You can't go ahead or astern very far because of the boat behind you and the one ahead of you. How are you going to get out of this fix? Again, spring lines are the answer.

If circumstances favor your pulling out and moving ahead, run a long spring line from a cleat on your port rail astern to a piling or cleat on the fuel dock well forward of your position.

Let go your bow and stern lines. Now, with your wheel hard to port, put the engine in reverse and back the boat down. Like magic, your bow will swing out to starboard, clearing the boat ahead (you may need additional throttle if you're battling wind and current). You - perhaps aided by the dock attendant and/or a crew member-can now release the spring line and proceed out into the harbor.

When, on the other hand, circumstances favor your backing out of your spot, the spring line should be run from your bow to a piling or cleat well aft of your position.

In this case, let go the dock lines, turn the wheel hard to port (the side against the dock), put the idling engine into forward gear, and watch as your stern swings miraculously out of harm's way.

When it clears the boat behind you, momentarily shift into neutral, release the spring line (or ask that the dock attendant free it), shift into reverse, and back away smartly. Again, the peanut gallery will be very impressed.

Five Rules for Avoiding Injury

Before each docking maneuver, make sure everyone understands what he or she will be doing. The corollary to Rule 1 is that you should be aware of where your crew is and what each is doing.

A woman in California was securing a springline to a cleat when the skipper suddenly backed down hard with his two 200 HP engines and she got her fingers crushed. Another man was standing on the dock holding onto a trawler's bow pulpit when the skipper gunned the engine and yanked him into the water. In both instances (and many others) the skipper and crew were acting independently.

Don't encourage your crew to make Olympian leaps onto the dock. This is one of the most common types of accidents. A California man, to cite one example, broke both his heals when he landed on the dock after jumping from the bow of a large sailboat.

Whenever possible, hand docklines to someone on the dock. If that isn't possible, wait until the boat is safely alongside the pier before instructing someone to step ashore. Your crew shouldn't have to make daring leaps across open water to make up for your sloppy boat handling.

Keep fingers and limbs inboard! As a boats gets close to a dock, passengers tend to gravitate toward the rail and drape fingers, legs and arms over the side of the boat. If the boat suddenly swings into a dock or piling, the consequences can be painful.

A woman in lost a finger when a passing boat's wake slammed her boat into a piling, and pinched her hand between the piling and the boat.

Make sure everyone is seated or has something to hold onto. The owner of a 20' runabout asked his inexperienced nephew to jump onto the dock with a bowline. The young man eagerly climbed out of his seat and stood precariously on the bow as the boat was approaching the dock.

A few seconds later the boat glanced off of a piling, only slightly, but without a handhold the nephew lost his balance and fractured his elbow.

Don't use bodies to stop the boat. A Florida man suffered a separated shoulder when he tried to keep a 38' Sportfisherman from backing into a piling. Slow down and use fenders.