Engine Cut-off Devices

Foundation Findings #42 - November 2006

For Foundation Findings #42, we looked at lanyard-style kill-switches and Wireless Crew-Overboard Systems. For an overview of the results see below for the published article. For a more detailed account of our testing procedures use the buttons at left to navigate through our methodology or simply click Next below.

Kill-switches are a hot-topic these days. It seems that every boating magazine on the shelves is publishing the latest on these safety devices and their more sophisticated cousins, wireless man-overboard alarm systems. The big question is how do these new systems stack up against the more widely-used and well-known lanyard-style kill-switch. With new technology stocking the shelves every day we decided to add our two cents to the conversation for Foundation Findings #42. In the November issue of BoatU.S. Magazine you can find the condensed version of the testing results and our opinions on the benefits and limitations of various devices but for more details on the tests themselves and our experiences with kill-switch lanyards and wireless MOB alarms on the water, read on.

We tested four different lanyard kill-switches: Sea Dog Universal Kill Switch, Cole Hersee Emergency Cut-Off Switch, Sea Choice Kill Switch and Sierra Emergency Cut-Off Switch; and three wireless crew-overboard devices with optional kill-switch features: Emerald Marine Alert2, Maritech Safety Virtual Lifeline and Mobilarm MOBi-lert 720i. We also included two universal kill-switch key sets from Kwik Tek - one for PWCs and one for boats. With so many products to test and only one boat to test them on, we had to get pretty creative with the installation.

Artistic Installation

We mounted the four kill-switch lanyards to a piece of 25" x 6" Starboard, marine plywood, which was mounted to the helm station on the boat. Then all four switches were wired into the engine for testing. The whole procedure was relatively simple for even a novice electrician. If you have ever changed an electrical outlet in your home you can probably install one of these kill-switches. The only one that gave us trouble was the Cole-Hersee, which required drilling an oddly-shaped hole to accommodate its awkward profile. But its unusual shape is what makes it more convenient to use. Designed as a simple up-and-down switch with a protective cover surrounding it on three sides, it was the only kill-switch we tested that allowed the engine to be restarted without the lanyard attached.

The wireless systems were a bit more complicated. Using another piece of 20" x 27" Starboard, we installed the components of all three systems and ran all the wires along the back so they were exposed at the top of the board where we could use alligator clips to hook each system to the engine individually when we were ready to begin testing. It looks just as complicated as it sounds as you can see from the pictures here. You'll likely need to bring in a professional marine electrician for your installation for some of these models, especially if you plan to connect it to your GPS or chart plotter.

The Contenders

We tested four different lanyard kill switches: Sea Dog Universal Kill Switch, Cole Hersee Emergency Cut-Off Switch, Sea Choice Kill Switch and Sierra Emergency Cut-Off Switch; and three wireless crew overboard devices with optional kill-switch features: Emerald Marine Alert2, Maritech Safety Virtual Lifeline and Mobilarm MOBilert 720i. We also included two universal kill-switch key sets from Kwik Tek - one for PWCs and one for boats. We quickly realized that it is impossible to evenly compare the lanyard and the wireless systems. Each has its own ideal circumstances and potential limitations.

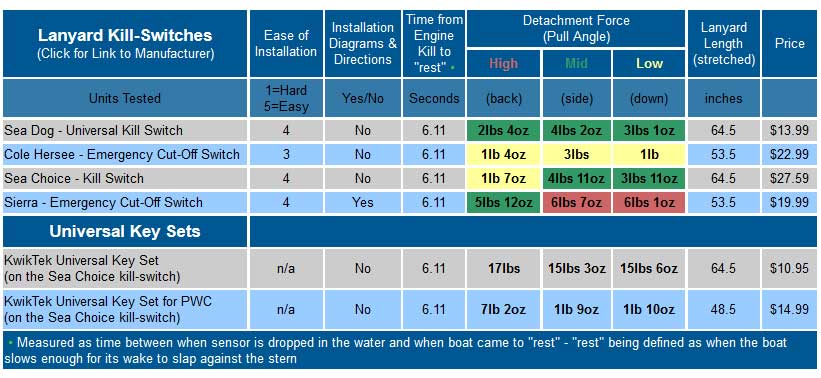

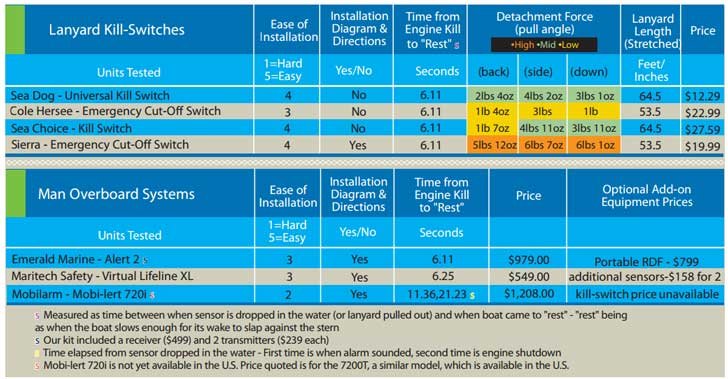

The variables investigated were ease of installation, the length of the lanyards, the force required to pull the key out from various angles and shut off the engine (lanyards), and the time it took for the crew-overboard devices to receive the signal to shut off the engine (wireless).

How Did the Lanyards Measure Up?

One of the primary frustrations with lanyard kill-switches is possibility of accidental engine cut-off. When the lanyard is attached to the pilot, the range of movement is limited to the length of the lanyard and the amount of force necessary to pull-off the kill-switch key. So this was the focus for our first round of testing. Once installation was complete we began recording measurements for the length of each lanyard when fully stretched, including the two universal kill-switch key sets.

Next we wanted to find out how much tension was required to pull each key off its kill-switch. We attached the end of the lanyard to a digital fish scale and recorded the weight displayed on the scale when pulling the lanyard key off the switch. We used a fish scale because it is something that many boaters can relate to. We repeated the pull-test from three different angles for each kill-switch - straight back, from the side, and down at a 45-degree angle. The results are displayed in the chart on the next page, along with the lengths of the lanyards. Of the lanyard kill-switches that we tested, the Sierra required the most tension to engage the kill-switch.

Of all the switches we tested, it registered the highest weights for each angle. So it would be the least likely to cause an accidental engine cut-off, but it was also the only kill-switch lanyard that didn't fit with any of the keys on either of the two universal key sets. One of the universal key sets had a key that was the same shape as the Sierra but was incorrectly sized and wouldn't fit. This makes replacing a lost lanyard a bit trickier. On the other hand, the Cole Hersee registered the lowest weights for each angle making it the most likely to cause an accidental engine shut-off. But that detail shouldn't deter owners of smaller boats. The other kill-switches won't allow the engine to be restarted without the key in place, but the Cole Hersee can be easily switched back to the "run" position without the key. This can be a great help if your helmsman goes overboard with the lanyard key attached. Unless you have a spare, you can't restart the engine to go retrieve him.

When we were performing our pull-tests one of our lanyards went flying over the side of the boat and sank in the water. To remedy that problem we secured the rest with a line, loosely tied so not to affect the test results. We subsequently realized that only two of the six lanyards we tested had floats attached - the Sierra and the Kwik Tek for PWCs. So a floating key chain will make a good accessory for your lanyard as well.

Setting the Standard

The effect of the lanyard kill-switch is immediate, meaning that the instant you pull the kill-switch key out the engine will shut-down. With the wireless systems we expected there to be a delay between the transmitter sending the signal to the base unit and the engine shut-down. So to more accurately measure the time it took to for the engine to cut we established a baseline standard with the lanyards.

With nearly ideal conditions, few waves and no breeze, we set out to test the lanyard kill-switches. In our 22' center-console with a single 200hp gas-powered engine, we took off on a plane at 35mph and pulled the kill-switch key out as we passed an anchored buoy we had set. We timed 6.11 seconds between when we pulled the kill-switch and when the boat came to 'rest'. We measured a distance of 125 feet between the first buoy and our 'rest' point. For the purposes of this test we defined the term 'rest' as the point at which the boat slowed enough for its wake to come back and slap against the stern. This will, of course, vary from one boat to the next as well as with differing conditions. We were lucky to have a steadily calm day throughout all of our testing - of course that made it incredibly hot and humid in the middle of the day on the Chesapeake Bay, but we survived.

The decision to use this concept of 'rest' as our basis for timing stemmed from the assumption that we wouldn't be able to accurately determine when the engine cut with each of the wireless devices. We could assume it would cut when the alarm sounded but that proved to be untrue with at least one of the systems.

Time Travel

We moved on to testing the wireless crew-overboard systems once we had established our baseline. Using the same procedure as for the lanyard kill switches, we accelerated to 35mph and dropped the personal transmitter for each of the systems when we passed the first buoy and times how long it took for the alarms to sound and the engine to cut bringing the boat to 'rest'.

The first two systems we tested were the Alert2 and the Virtual Lifeline. Both have transmitters that trigger a signal back to the base unit when exposed to water. The Alert2 matched the lanyards in cutting the engine. We timed 6.11 seconds between dropping the transmitter in the water and when the boat came to 'rest'. It also sounded an alarm the instant the transmitter got wet.

The Alert2 offers features that make it a good choice for coastal/offshore boating. It has a number of extra features such as an optional radio direction finder (RDF) which enables the user to search for the transmitter's radio signal when retrieving the crew-overboard. This could be a life-saving feature in rough conditions or low visibility. It also has the ability to be wired into your GPS and chart plotter to mark the position where the crew-member went overboard. As with any GPS man-overboard waypoint, it cannot account for drift occurring after activation.

The second system we tested was the Virtual Lifeline which also had a quick response time similar to the lanyards. Its water-activated sensors immediately sounded an alarm and quickly cut the engine when submerged. We timed 6.25 seconds between dropping the sensor in the water and 'rest' - just a hair longer than the Alert2 and lanyards. It is an excellent choice for use with families and larger groups that are boating on inland and protected waterways. Its water-activated sensors can also be used as a precautionary mechanism. When swimmers are in the water they could each wear one of the sensors so you can't restart the engine until everyone is on board.

Both of these water-activated models caused us to question the likelihood of false activation from rain or spray. We tested the transmitters of each and found out that they must be submerged to activate. Each one has safeguards built-in to prevent a false activation from a small amount of water from normal boating spray. The Alert2 has a protective holster which covers the sensor and the Virtual Lifeline has a similar protected entry point for water.

The third wireless unit we tested, the MOBi-lert, is primarily a crew-overboard alarm device that works by sensing a disruption in the radio signal between the sensor and the base unit. This occurs when the sensor goes outside the range of the signal or is submerged in water. The kill-switch unit that we tested was a prototype made specifically for us and is not yet commercially available. The manufacturer said that the unit may be released as an optional add-on for retail sale later in the year.

According to the manufacturer, there is a built-in delay to prevent a false activation, and a second delay on the engine cut-out unit. We timed 11 seconds between the time the sensor went in the water and the alarm. Ten seconds later the engine cut and the boat came to 'rest'. This convenient delay between alarm and engine-kill allows the boat operator to turn back and pick up the crew-overboard without having to restart the engine. Since the MOBi-lert's multiple sensors are always on, you'll always know when your crew is on board. You could even use it to keep track of your crew when in port and make sure you don't leave anyone behind.

The MOBi-lert is well-suited for coastal and offshore boating as it can also be connected to a GPS or chart plotter and will automatically trigger a crew-overboard waypoint if someone falls into the water.

In testing the three wireless crew-overboard devices we found that each has features suited for different boating conditions. Offering more convenience than lanyards, all three provided multiple sensors that could be worn by each person on board. Lanyards only protect the helmsman and you have to remember to detach and then reattach it every time you step away from the steering console. The wireless units can be attached at the beginning of your voyage and left on for the duration of the trip. Each system also had a "rescue mode" to disengage the kill-switch, providing for engine restart and crew-overboard retrieval.

Wrapping It Up

There are other systems out there that function as crew-overboard alarm/alert systems but do not have kill-switch features. For the purposes of this Foundation Findings we limited our tests to those with an engine cut-off. Landfall Navigation has a good selection of crew-overboard devices currently available in the U.S.A. Companies around the world are introducing new products each year to help keep you and your crew safer.

There is no single device that is perfect for every situation. Each has advantages for specific boating conditions. A lanyard kill-switch is a must for anyone boating solo or operating a PWC, but it only provides protection if you're wearing it. If the helmsman has to attend to something out of reach, it would have to be detached to avoid accidentally killing the engine. To prevent loss of power at a critical moment it should not be worn in an emergency situation or while docking.

The wireless systems provide a safeguard for the entire crew. Each has features suited for a particular environment and should be used in addition to your life jacket and other safety gear. The systems might also be used in conjunction with a lanyard. In a situation where the helmsman is simply thrown from his seat and not into the water, only a lanyard will kill the engine giving the pilot time to recover control of the boat. In sum, the most important factor to consider before making a purchase is the kind of boating you plan to do.

- By Amanda Suttles