Steady As She Goes - Stabilized Binoculars

Foundation Findings #35 - November 2001

Unless you do your boating from the bridge wing of a Navy destroyer, chances are the binoculars you use get the jitters. When you need them the most, it seems - to read the number on a channel buoy, sort out the lights on an approaching vessel or read the name on a pitching transom - conventional binoculars just leave something to be desired.

The human hand just can't hold binoculars steady enough for most maritime applications beyond seven-power magnification but it's not the glasses. It's the swell, it's engine vibration, it's boat speed - most of all, it's you.

That's why 7x50s (seven times the magnification with a 50-mm objective lens for optimum light gathering), has become the standard for recreational boaters.

If you've been boating for awhile, there doubtless have been times when you could really use those big gyroscopically stabilized binoculars that the U.S. Navy has used for years. They have very high magnification and make everything hold still. Yet binoculars that could lock on to what you really need to see have been out of the reach of most recreational boaters.

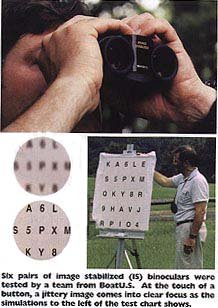

But thanks to Image Stabilization (IS) technology developed to take the shakes out of hand-held video recorders, affordable binoculars are now coming on the market that either mechanically or electronically dampen movement, seeming to lock on an image. Thus, IS binoculars allow boaters to opt for higher magnification. And since the number of available models is going up while prices are coming down, we thought it was high time to focus on these new devices.

How Do They Do That?

In general, IS binoculars stabilize the image by manipulating the lenses to continuously compensate for movement of the device in your hands. This is achieved using an internal gyroscopic mechanism or with electronic sensors coupled to microprocessors that instantaneously adjust for any motion.

Basically, what you are looking at stays still in the field of view although the compensating function takes some getting used to. Of the units we tested, two used the gyro system that requires no batteries and five used the microprocessor, which does. (It's important to note that all these binoculars function in conventional mode until the IS feature is enabled, even if the batteries are dead.)

We tested six products from four manufacturers, Canon, Fujinon, Rigel and Zeiss, ranging in price from $430 to $2,500 and with magnification from 10-power to 20-power.

For comparison purposes, we included a tried-and-true pair of non-image stabilized 7x50 binoculars from Tasco, the Offshore 21 model. This particular pair rated quite high for their $150 retail price in our 1995 test of conventional binoculars. We felt this product represented the typical binoculars found on many recreational boats today.

The Eye Team

Three experienced boaters with many hours of peering through conventional binoculars made up our team of testers. They ranged in age from their early 30s to the early 50s and each tested to 20-20 vision, or very close to it. In other words, our Eye Team did not use any corrective eyewear during the test.

We created 20"x 30" eye charts with five lines of black letters and numbers, five per line, on a white background. We chose a simple 2-inch block letter in the same style that the U.S. Coast Guard and most state marine agencies use to identify navigational aids.

Next, we laid out an on-land test field marked off every 100 feet, beginning at 200 feet and running to 1,300 feet, just shy of a quarter mile. The test began with the eye charts at 200 feet and all testers reading them using the conventional 7x50s. A recorder assigned to each pair of binoculars tabulated scores and took down comments.

The charts were changed to ensure that Eye Team members would not unconsciously memorize lines as they looked through each pair and read a line on the chart. A perfect score was five out of five figures read correctly. Below a composite 86% accuracy score, we pulled the unit from the test.

By 400 feet, the scores of the conventional binoculars began dropping. Beyond 600 feet, the 7x50s were out of the running (our testers were getting testy, anyway, from all the eye strain) but the IS units were just beginning to hit their stride.

After 1,200 feet, double the distance at which the conventional binoculars quit, the competition began to thin out. Here we switched to charts with 1-1/2-inch figures, re-testing at 1,200 and 1,300 feet.

Wow!

By the time we got toward the end of the test, the Eye Team could barely see the technician in the field changing the charts with the naked eye. Yet with the IS binoculars, they could read numbers and letters smaller than those on a car license plate - from four football fields away.

To put it mildly, our reviewers found IS technology, well, eye opening. But once beyond the initial "Wow!" stage, our testers became very adept at operating each unit and in evaluating its strengths and weaknesses for boating.

Regardless of the particular model, our testers found that as distance increased, it took more time and concentration to focus the binoculars in order to take full advantage of the IS feature.

The three Canon models tested have center focus dials and look and feel most like traditional binoculars. All had excellent optics and good design for ease in focusing and engaging the IS feature. The first we looked at, the Canon IS 10x30 ($430) proved lightweight and easy to use but as distance increased, focusing got harder. They represent an excellent value in the lower magnification range but lack of waterproofing was a big concern.

The Canon IS 12x36 ($750) is a step up but frankly, we're not sure the two-power magnification gain is worth nearly double the price of the smaller Canons, particularly since these are not waterproof either.

At the next increase in magnification, the Fujinon TechnoStabi 14x40 ($1,100) offers outstanding stability and a sharp view. The shape of the waterproof "Fuji s" felt more like a video camcorder and operating it took some getting used to. These are probably best suited to a larger boat with a roomy helm station. (Fujinon also offers a professional grade StabiScope in 12x40 and 16x40 sizes. While not included in our test, we did get our hands on the 16x40 model carried on NASA's Space Shuttle. Now we know why.)

The increased magnification offered by Canon's IS 15x50 ($1,300), coupled with waterproofing and a bright view, made this model the top choice if cost were not a factor. Also in this category, the non-electronic Rigel 9100 16x50 ($540) is the least expensive of the higher magnification models. In use, our testers found that the image "swims" as the mechanical stabilizer catches up. While rather heavy and difficult to focus, they are waterproof and at half the price of similar size binoculars, they are worth consideration.

The Zeiss IS 20x60 ($3,000) we tested was a monocular. While some old salts may still use a spyglass, this is not a design we would recommend for boaters today since binoculars are the norm. It lacks an eyecup, which lets light in, but it uses the same lenses and non-electronic IS system as the binocular version ($5,000) which we were not able to test. The monocular produced a very bright, clear image, however, and we would assume the binocular model of the same power, which does have eyecups, would too.

Observations

IS binoculars are relatively new to boating and many different models are being introduced, seemingly to test the market. We suspect that two or three sizes will emerge as "standards" for boating. Size and weight should come down, too, and we certainly hope that more waterproof models will be available in the lower power sizes soon.

There appears to be no real track record yet for IS binoculars in terms wear and tear and cost of repairs to help guide the consumer. For the electronic models, battery life is a concern - keep spares at hand. Size, weight and complexity of operation seem to increase along with magnification.

Even on the low end of the price spectrum, IS binoculars are revolutionary and unless money is no object, even the smaller models are a huge improvement over hand-held binoculars. The only caveat here is the limited number of waterproof models available.

Weight and overall size is a consideration and we think it would prove cumbersome to keep some of the larger models around your neck for any length of time, particularly on a pitching boat. The gyroscopically stabilized models, by the way, reportedly provide added compensation for movement of the boat under you.

Our advice is to think about how you use your binoculars today and consider how much of an increase in magnification would be desirable to help make your kind of boating safer and more enjoyable. Then focus on IS binoculars as the way to do it.